Chang Cheh (張徹) — The poetry of violence

Stefan Hammond*

"Chang Cheh made One-Armed Swordsman in 1967 and wiped Cantonese films off the face of the map".

— Shaw Brothers director Chor Yuen (楚原)

Chor was dramatic but also disingenuous. His own House of 72 Tenants (七十二家房客,1973) featured Cantonese dialog and was a hit for Shaw Brothers.

But Chang — (張徹), born in Zhejiang in 1923 — was both traditional and transgressive. His martial arts heroes embodied yanggang wuxia (陽剛武俠): masculine martial arts. This ran counter to the film heroines of the time: Connie Chan (陳寶珠) and Josephine Siao (蕭芳芳) at rival studio MP&GI, and Cheng Pei-pei (鄭佩佩), star of King Hu's legendary swordplay epic Come Drink With Me (大醉俠, 1966).

Watching One-Armed Swordsman nowadays (preferably on high-definition Blu-ray on a large screen TV), Chang's nascent directorial style is on full display: masked combatants, handheld camera work, a twisty plot, and a heaping helping of cinematic violence. Many of these elements helped inform one of Chang's apprentices at Shaws: John Woo (吳宇森). Chang smashed existing film canons, piled up box office lucre — OAS was the first Shaws film to gross over a million Hong Kong dollars and went on to direct star Wang Yu (王羽) in The Assassin (大刺客, 1967) and Golden Swallow (金燕子, 1968), the latter paired with Cheng Pei-pei.

Renaissance man

How did this upstart — a Chinese storyteller who loved brash Hollywood stars like James Dean and Marlon Brando — manage to carve his name in the martial arts cinedrome? Shaw Brothers at the time focused on romantic comedies and musicals, many directed by their in-house Japanese directors, a triumvirate spearheaded by Inoue Umetsugu, who lensed fluffy dramas like Hong Kong Nocturne (香江花月夜, 1967).

Chang was a scholar with a poetic streak (he wrote lyrics to songs in some of his later films) who worked as a film critic. His reviews caught the eye of Run Run Shaw (邵逸夫), who hired him to direct. After a maiden effort (Tiger Boy, 虎俠殲仇, 1966), a film which is unfortunately lost), Chang pointed his lens at Taiwanese leading man Jimmy Wang Yu, chopped Wang's arm off, and raked in box office lucre. Chang revisited his triumph with later films like Return of the One-Armed Swordsman (獨臂刀王, 1969) and New One-Armed Swordsman (新獨臂刀, 1971).

Deadly duo

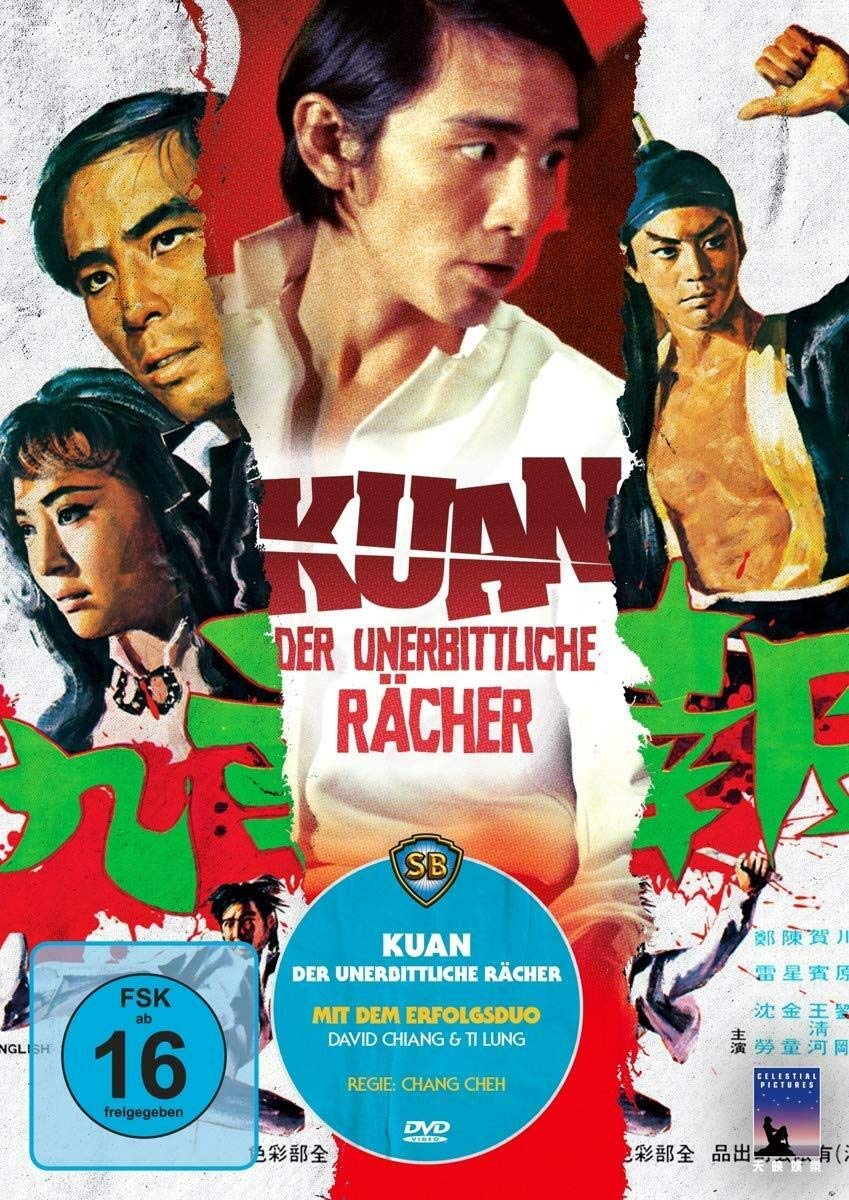

In the late 60s, Chang formed working relationships with David Chiang (姜大衛) and Ti Lung (狄龍) — stalwart Shaws actors who ran a gamut of roles under Chang's direction. 1971's The Angry Guest (惡客) was shot in Bangkok and showcased one of Chang's few film appearances, as villainous Japanese boss "Mister Yamaguchi".

The acting pair wowed audiences in films like The Deadly Duo (雙俠, 1971) and 1970's Vengeance! (報仇), where director Chang's heroes wear all-white to better show off the liters of stage blood.

Masked martial mayhem

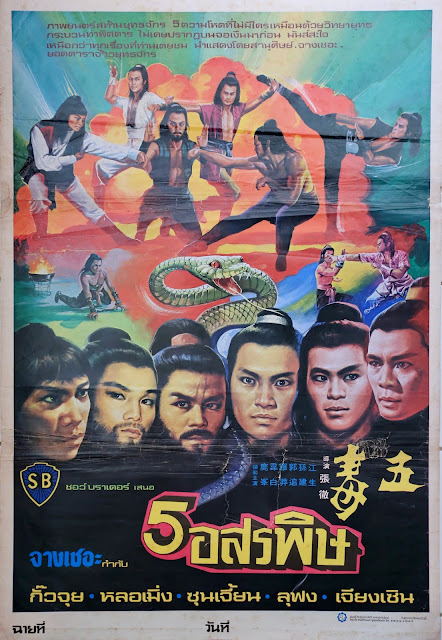

In 1978, Chang directed one of the era's better known martial arts epics: Five Venoms (五毒, 1978). The film showcases martial acrobats whose personalities dissolve into their fighting styles — because they wear masks to hide their identities. FV was dubbed into English and became a massive worldwide hit.

Chang's visceral vortexes of violence were a draw, but he also made dramas like Young People (年輕, 1972), The Delinquent (憤怒青年, 1973), and The Generation Gap (叛逆, 1973), all of which highlighted social tensions in Hong Kong society. And Chang wrote lyrics for several of his films, including The Singing Killer (小煞星, 1970) and Heaven and Hell (第三類打鬥, 1980).

The latter, also known as Shaolin Hell Gate, featured several of the Venoms Team: Five Venoms alumni, mostly Taiwanese. Chang and this core team relocated to Taiwan in the early 80s. His final film for Shaw Brothers, the Hong Kong studio that brought so many of his tales to celluloid life, was The Weird Man (神通術與小霸王, 1983) — a mix of furious martial arts and Taoist hijinks.

The final word on Chang belongs to director John Woo, who paid tribute to his mentor in Chang Cheh: A Memoir, published by the Hong Kong Film Archive in 2004. "Chang Cheh managed to make us feel that filmmaking was fun, spiritual, almost poetic, and a dignified pursuit," wrote Woo. "Looking back, Chang Cheh not only taught me how to direct, but also the way of life."

*Hong Kong-based writer and film critic

N.B. Photos of the three movie posters in Thai, German and Spanish provided by the writer