Yuan Quan and Jing Huaiqiao

SHENZHEN – Four years ago, after returning from abroad, Chinese entrepreneur Liu Yang and her husband started a business manufacturing medical machines that offered a chance of life to people who would otherwise have died.

In recent months, the English acronym for these machines has appeared often in Chinese media. Stories of critically ill COVID-19 patients who have survived on ECMO devices make front-page news, where it is hailed as a “miracle machine.”

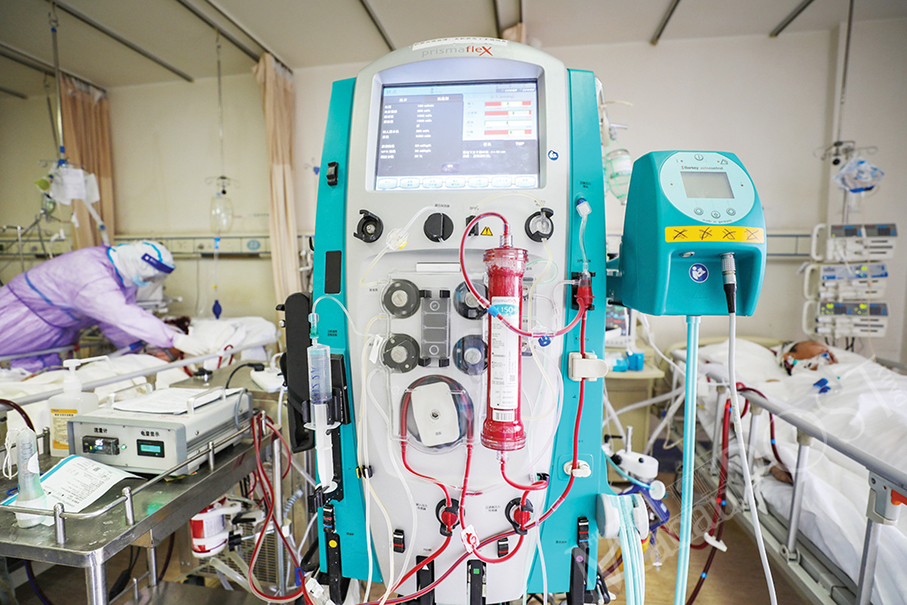

ECMO, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, is a technique that provides prolonged cardiac and respiratory support to patients whose heart and lungs are unable to work.

ECMO was previously commonly used in open heart surgery, but its use has skyrocketed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Though very expensive and labor-intensive, it is widely viewed as a last-ditch treatment. Studies have shown that ECMO can greatly reduce mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients.

Currently, China’s ECMO machine market is dominated by one US and two German brands. According to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), 67 ECMO machines were sent to treat severely ill COVID-19 patients in Hubei province in March, and 29 were bought from abroad as an urgent matter.

“We will do whatever it takes as long as there is a glimmer of hope,” said Wuhan surgeon Dong Nianguo. In May, one of his COVID-19 patients received a double-lung transplant after 73 days of ECMO therapy and survived.

The record was broken in August by a 62-year-old COVID-19 patient in Guangzhou who survived on ECMO for 111 days.

“I was very impressed by the efforts to save lives at all costs, and I was aware that our company has a social responsibility too,” said Liu, chairman of Chinabridge Medical Group, a Chinese ECMO machine manufacturer.

Over the past four years, Liu’s company has been at the forefront of China’s development of core parts of the machine, including the oxygenator and centrifugal pump, which function as an artificial lung and an artificial heart. Some have been patented globally. She plans to conduct clinical trials in two years.

Liu and her husband Li Yijiang spent 16 years in Germany and returned to Shenzhen in 2016. A heart surgeon at Shenzhen Hospital of Southern Medical University, Li believes the use of ECMO is necessary, but many local hospitals do not have it.

ECMO is rare across China. A few hospitals imported ECMO machines after the SARS outbreak in 2003. According to the Chinese Medical Doctor Association, about 400 ECMO machines were used in 260 hospitals at the end of 2018.

The high cost of ECMO is generally unaffordable. An imported machine is priced from 1 million yuan to 3.5 million yuan. It includes a complex circuit of pumps, tubes, filters and monitors. Generally, the cost of two weeks of treatment is 100,000 yuan.

The labor involved also makes the treatment expensive. A person on ECMO cannot live outside the intensive care unit and must be continuously monitored for complications, such as blood clots, bleeding, infection and loss of circulation to the limbs.

The median cost of ECMO is 200,000 yuan in China, making it one of the most costly medical procedures, said Liu.

Such a cost scares away many poor families and China’s medical insurance does not cover the treatment.

There are still medical professionals who don’t fully understand what it can do and how to use it, said Liu. In addition, some argue the so-called “miracle machine” is not always successful. Liu cites foreign data showing about half of patients who require ECMO will survive.

“The first year was very difficult,” Liu recalled. The company had trouble getting financing and partners, as well as recognition.

They thought of giving up, until Li used ECMO to save a young woman with acute respiratory failure in 2017.

“The patient was in a critical condition after my team used all other possible therapies,” Li recalled. “We decided to try ECMO and asked many hospitals for help, including those in Hong Kong. At last, we found a machine and put it in the ICU.”

After seven days, the patient recovered. Her parents burst into tears.

“We set our minds on developing China-made ECMO machines, no matter how difficult,” Liu said.

She spent months convincing leading German clinicians and medical engineering experts to work with them and their experience is the core competence of her team.

Taking advantage of Shenzhen’s innovation strengths

Liu expects her company to take advantage of Shenzhen’s innovation strengths, which rival Silicon Valley, as well as its low manufacturing and assembly costs.

China-made ECMO machines should not be just copies of foreign products, she argues, but should be “a next-generation life support machine that is cheaper, lighter and easier to operate, to help doctors save more people.”

For example, her company, under the brand name Lifemotion, wants to create a smaller-than-normal device which is light enough to be transported in an ambulance, making it possible to provide ECMO support in emergencies.

COVID-19 has increased competition for ECMO manufacturing. In March, a team at Shandong University announced it had developed a machine at a lower cost than foreign brands and is expected to move into mass production; in August, a medical technology company in Jiangsu province independently developed a portable ECMO system called the Saiteng OASSIST ECMO, which has begun the registration process.

Governments have also stepped up support. The medical equipment department Guangdong province has discussed providing technical support to ECMO enterprises in a bid to push forward domestic manufacturing.

In September, the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) announced it will invest 20 million yuan to support research and development.

Many hospitals in Beijing have launched programs to train staff in the use of ECMO machines. Liu’s company is also gaining recognition at home and abroad.

“There is still a long way to go to develop ECMO machines domestically, but I believe it is just a matter of time,” said Liu. – Xinhua

A nurse adjusts an extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation machine (ECMO) used by a critically ill patient in the temporary intensive care unit (ICU) ward at Wuhan Red Cross Hospital on Feb 28.

Photo and caption courtesy China Daily