Interview and review by Ginnie Liang

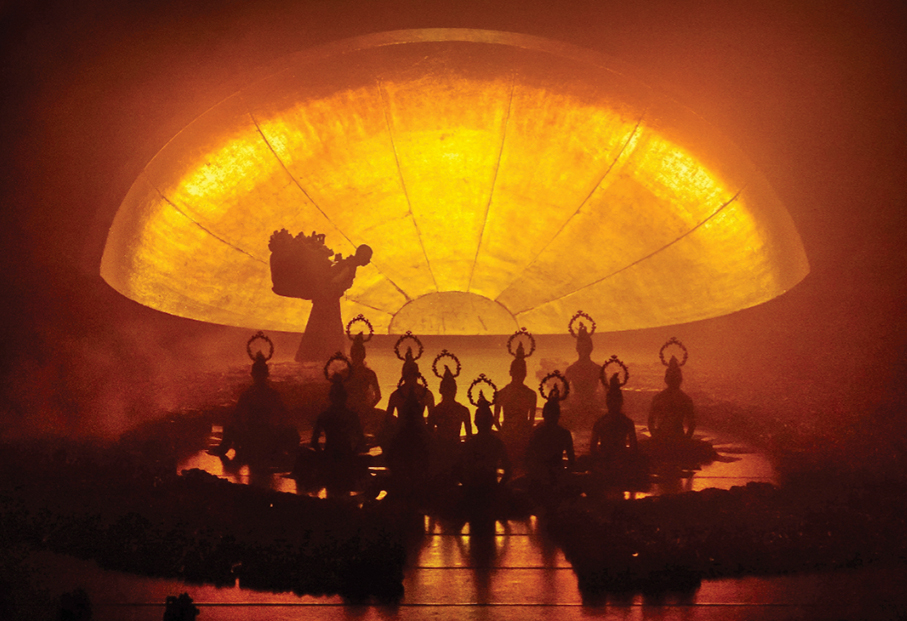

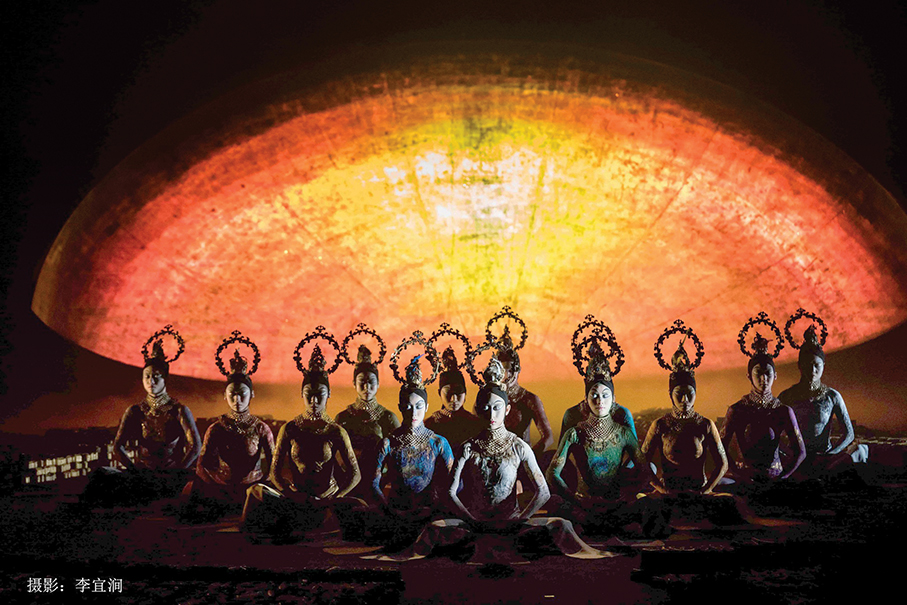

The 33rd Macao Arts Festival (MAF) opened on April 28-29 with Rite of Spring, which utilised Stravinsky’s iconic score alongside original compositions from over 100 years ago, for which numerous dance artistes have created choreographies. Renowned mainland Chinese dancer Yang Liping’s version of Rite of Spring, regarded as a pioneering work of Chinese modern dance ever since its launch for integrating Oriental philosophy, symbols and aesthetics, was staged to a full house at the Macau Cultural Centre (CCM) on two nights.

Yang, known for her peacock dance, was the director and choreographer of the show, along with the show’s three principal dancers talked about the making of the Rite of Spring with members of the general public as well as journalists at MGM COTAI on April 27.

A litmus test for an artist

Yang said, “I was very interested in creating a dance to this music and to be honest, I also found it very difficult because there are already so many dance versions that interpret such a classic piece of music in a different way. It’s such a challenge for the choreographer”.

To contribute to the full-length dance theatre production, Yang invited He Xuntian – a renowned mainland Chinese composer – to create “groundbreaking” contemporary music that incorporates elements of Tibetan and other ethnic music, as well as a “dialogue” with Igor Stravinsky through the music.

Yang said that “in all the dance versions, the sacrificial girl is passive, feeling both glory and fear, which is extremely contradictory, and ultimately being trapped in fear. However, in an Oriental perspective, one is encouraged to devote and sacrifice oneself for the good of the tribe.

“Finally, the person who is sacrificed will be reborn,” says Yang, referring to the traditional worship rituals of China’s ethnic minorities.

Music plays the soul

The music throughout the play was sometimes soft and sometimes titillating, with ancient Tibetan strings and percussion creating a rich rural atmosphere.

In order to show the coupling of the male and female protagonists, some heavy drum beats sounded like heartbeats and at times faintly merging into intimate whispers, while the extremely fluid bodies of the male and female dancers softly and powerfully complemented each other.

Throughout the play, there was powerful musical accompaniment whenever the High Priest, played by Da Zhu, appeared. As the only male dancer in the play, Zhu said he felt “excited” at first, but then felt a great challenge.

“Yang told me that I’m not just a character. Because I need to start as a human and then become an animal. And from an animal, I need to die and be reincarnated, and finally to perform the sacrifice,” Zhu said.

Never had I heard such a resounding silence – as the dancers paced frantically, their heads tossing and gasping in tribute to the young girl chosen as the sacrificial victim, who danced until she died.

Then suddenly the music stopped and all that remained in the theatre was the sound of gasping and violent pacing, speeding up, then slowing down until exhaustion set in. Then it accelerated to the heroine, the lights slowly focused on her as it seemed she was taking her last breath, the sacred holiness and fear of herself magnified in this moment.

Maya Dong, who plays the sacrificial girl, said: “Playing the lead role for the first time was very stressful for me. I remember I was crying on stage. I didn’t know what was happening and I didn’t really know how to handle this music. It was so powerful. When I tried to fight it, I couldn’t overcome it”. Dong recalled: “I remember one night I was dancing till throwing up and I felt like I was exhausted like dying.”

The power of sacrifice

Throughout the performance, a monk silently picked up the Buddhist six-syllabled proverb word cards (Oṃ maṇi padme hūṃ) – their literal meaning in English has been expressed as “praise to the jewel in the lotus” – and placed them in circle all over the stage, surrounding the dancers.

By using a large number of word cards to create a circle that narrows bit by bit, in sync with the dance, it showed a growing sense of urgency, indicating the inevitable outcome of the story – the sacrifice of the heroine.

This repetitive movement of the monk was also symbolic of the ancient village civilisation, which repeats itself like sunrise and sunset without any interruption.

Yang explained that the dancers needed to meditate for 30 minutes before the dance started, even as the audience were entering the theatre. Therefore, Yang’s team created the make-up – a third eye on the eyelid – to suggest that dancers can “see with their eyes” even when they are closed. “The dancers should feel the air, empty their hearts before they get started.” Yang said, expressing her special gratitude to the show’s visual director Tim Yip.

The ancient worship ritual couldn’t help but be frightening and mysterious at the same time. At the end, the entire circle made of the six-syllabled proverb word cards was destroyed – which is just like life itself, in its final inexorable decline.

The heroine, however, slowly flew into the giant golden disc and was then reborn in the golden powder waterfall. This surreal ending completed the people’s beautiful imagination of the sacrificial ceremony.

Movement, and silence, just like yin (陰) and yang (陽) – a Chinese philosophical concept that describes opposite but interconnected forces – all in one performance. It is the supreme love of life, but also the absolute madness of faith and art.

This undated file photo shows mainland Chinese dancer Yang Liping.

All photos provided by the Cultural Affairs Bureau (IC).